The current model of trustees isn’t suited to progressive, community-centred work and too often results in the same sorts of people overseeing strategy at arts organisations, argues Slung Low Artistic Director Alan Lane. If we’re not happy with how things are, is there a better way?

In any organisation there is responsibility, knowledge and authority: where it sits, who it sits with, and the relationship between the three tells us how an organisation works and its values.

There’s a very good book about leadership called Turn the Boat Around. It is, somewhat improbably in this context, by a US Navy nuclear submarine captain – David Marquet. He talks about the need to take authority and get it as close to those with the knowledge. One of the central ideas is that the best person to decide something is the person with the working expertise. It sounds pretty obvious, but it isn’t how most of our systems work. And it certainly isn’t how governance and authority work in the subsidised arts.

The vast majority of the publicly subsidised arts are made up of organisations that are formed as companies by guarantee and/or charities with a board of independent trustees at the top of the structure.

These trustees are traditionally drawn from a range of professional worlds: there’s normally a finance person, a lawyer, a couple of people from business, a fundraiser if you are lucky. They have the final authority over the organisation, they hire the Artistic Director and Chief Executive. They’re the big cheeses.

These are unpaid positions. It can be quite time consuming. It’s a lot of responsibility. There are quarterly board meetings with large amounts of information, often detailed financial data. Trustees also tend to be quite anonymous. Given how important their role is to cultural national life, you would expect trustees to have prominent profiles, but you would be hard pressed to name many. They also tend to be people (for all the reasons above) who have already done very well out of the system. The great and good. That’s who you need on your board.

In the last round of funding for members of the National Portfolio Organisations (those who receive regular funding from the Arts Council England), the recommendations advised that a ‘well-run’ organisation meant being a charity or a limited company with an independent board of trustees. This is the gold standard, it is believed. At the very minimum – “For the Arts Council, one of the characteristics of a ‘well run’ organisation is that it has a board or oversight group that is independent of the executive and can take responsibility for ensuring the efficient and effective delivery of the organisation’s funding agreement with us. “

An awful lot of the best of the changes in the arts sector – not least in the Arts Council’s own brilliant Let’s Create strategy – have at their heart the beliefs that we must remove the barriers between artist and audience, to understand that our communities are more than customers, and that our arts organisations need to be in service to those communities.

And yet here we have a governance structure that calls back to the 19th century model of oversight, of a distant ruling class: a governance system that doesn’t mind that those overseers have no professional expertise in the arts, or knowledge of the communities their organisations serve. It is the system of governance that has overseen the last half a century of subsidised arts, and I don’t think the collective performance of that sector has been good enough to see its governance structure protected, let alone lauded.

For the Arts Council, one of the primary benefits of this approach (don’t worry, I asked them) is that it results in a group of people in charge that they can liaise with if there is a failing culture within the organisation and within the Chief Executive. Because before now, it was the job of the Arts Council (or so, in reality, it came to be) to hold organisational leaders to account; now they would like the boards to do that more.

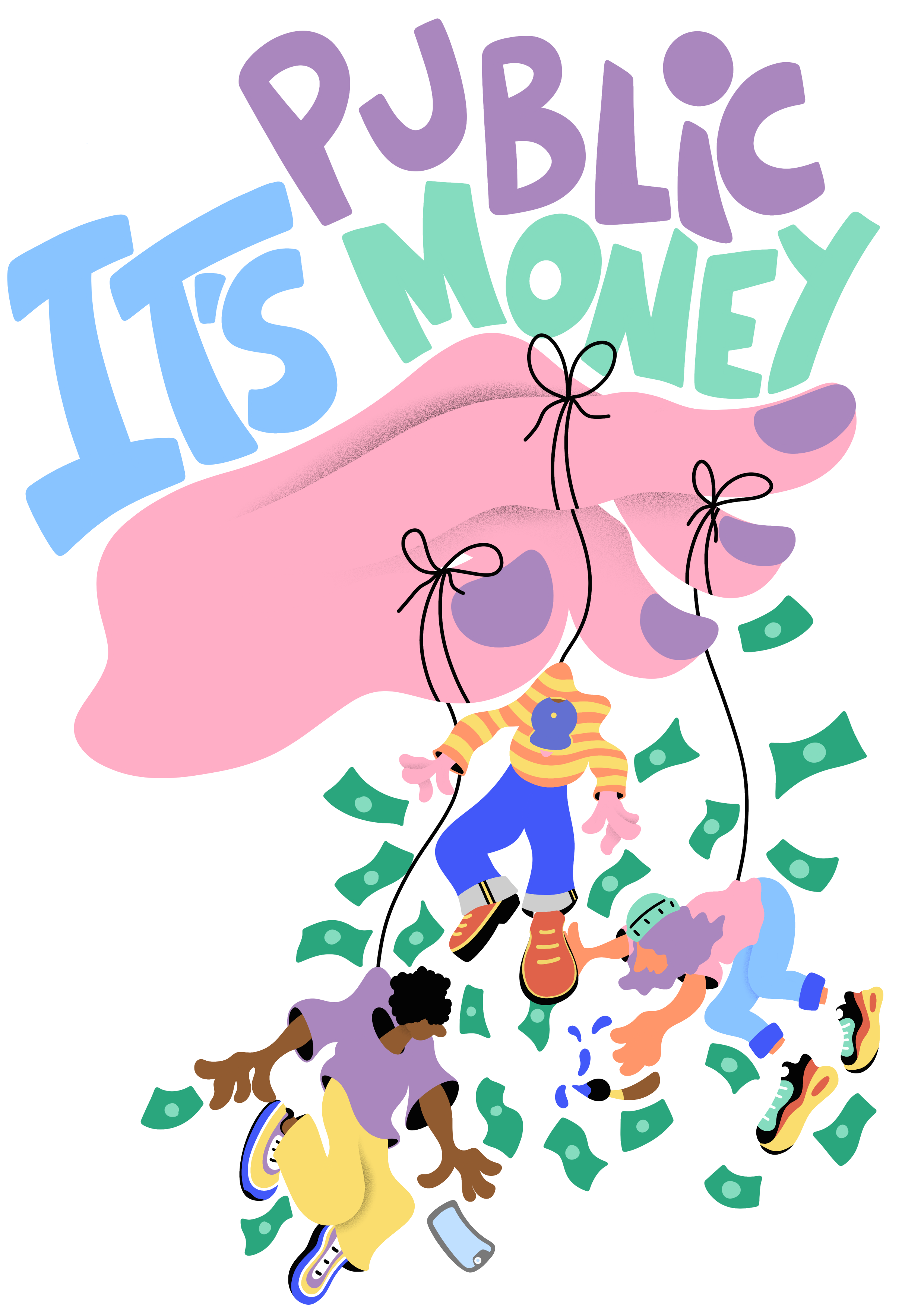

The idea that artists can’t be trusted has grown and evolved with the increase of administration and bureaucracy to the point that those in charge of our arts organisations need a moral handbrake in case the worst should happen.

And the driver for this caution and concern is because it’s public money that underpins the subsidised arts sector. The recent Conservative governments have used the argument of ‘it’s public money’ to bring arts organisations more and more under the control of the government. But it strikes me that the armed forces, the NHS, the police, indeed government itself, involve huge amounts of public money that must be protected, yet none of them have an oversight structure made up of a non-paid, non-expert class at the top of the organisation. In this context, you don’t have to be the most cynical of minds to see this new focus on a ‘gold plated governance standard’ as part of a continued desire by the Department of Digital, Culture, Media and Sport to grab more control of the nation’s culture.

Our funders and communities demand that we do things differently, in a more connected manner; we have, as a sector, turned to an already old, distant and disconnected form of governance. If you keep doing the same things and expect different outcomes, then you’re not paying much attention. And there are enough conservative tendencies in the trustee model for us as progressive theatre makers interested in how the arts can be a tool for social change to wonder what the alternatives are.

In fairness, this traditional model has such a prized place in our industry because no one within the sector (or at least within the mainstream part of it) has spent much time thinking about what alternatives might look like and, if we’re honest, because too many artist leaders don’t care. Because it’s not the art. It’s not the relationship. It’s not the connections. It’s not the community. However, it’s important because it’s the portal you now have to enter in order to get the regular funding that’s been traditionally kept from our communities and because ‘I don’t care about governance’ is something that a Bond villain would say. Both these reasons are compelling arguments for getting involved in governance. There’s a vacuum. It’s being filled by others.

At Slung Low, we’ve thought a lot about this tension between authority, knowledge, and responsibility. The privilege of an artist is to be responsible. Taking responsibility for keeping promises to our communities is something that we take very seriously. But we also know that in the arts – particularly in the arts – there are many examples of artist leaders who, without checks and balances, become perverted versions of themselves over time: perpetrating abuse of power, unaware of their communities, alive to their own qualities and no one else’s.

There is a need for balance.

Slung Low also recognise that there is a potential for conflict. We are in service to a community. We respond to their needs, but we also respond to their demands and create contexts for those demands to be solicited – we ask them what they want, and then we do it (in all sorts of fun and interesting ways). And what happens when the interests and demands of that community are in opposition to our board? It’s naive to think that a group of people whose focus is on the long-term security of an organisation will always be in sympathy with the immediate demands of a community like Holbeck, where we are based. If we have two masters, and they have equal authority, we’ll find ourselves in conflict.

The answer seemed simple enough: make a board of our community, neighbours and artists.

But asking people to take legal and financial responsibility for an organisation with a turnover of hundreds of thousands of pounds in complicated funding arrangements with multiple government organisations and trusts is not the gift people think it is. The sort of people who are comfortable with that are the sort of people you traditionally find on a board (which is why they are there): people with substantial cultural capital who have already done very well out of the current system, thank you very much.

We don’t have many of those in Holbeck. The current system of power and cultural capital does not work for us in Holbeck. If it did, we wouldn’t be here.

We needed to find another way.

So, we created a Community Advisory Board (CAB), made up of neighbours and artists, as the top of our Governance tree. They had no legal responsibility for the finances or risks of the company. And as a result, the group was much more diverse, more open. It was also much more immediately accessible because the usual paperwork and admin that comes with being a trustee were missing, so a whole range of people (who might otherwise be put off) took part in the advisory board.

They are given total authority. They have full access. Full trustee privileges. And what they ask for is actioned in a more responsive way than if they had been a traditional board. The company had to be attentive and reactive if the advisory board was going to have the status needed to be our governance authority, in large part because they didn’t have the legal status. Our CAB is diverse, supportive, demanding – everything we hoped for.

But we’ve realised that in the long term, this is no perfect solution for two reasons.

Firstly, part of what the CAB is about, and Slung Low’s mission more generally, was the increase of cultural capital and leadership in Holbeck. The CAB was a part of developing individuals into roles of leadership. With that development element, the CAB is never going to be truly challenging in the way that the best governance structure might.

It’s also because there is an outward-facing role for any governance structure. Our structure required an understanding of (and value given to) the individuals involved, the nuances, the specificity of the community and our role in it. It also requires huge amounts of good faith and trust. Without legal standing, it’s an act of collective faith by everyone involved, in everyone involved. So, when funders ask ‘how do we know these people really have authority? How do we know that it isn’t a trick?’ then it all falls apart. Because there is absolutely no point to any of this not being real EXCEPT to somehow pull a fast one on funders – to avoid the thing they have asked organisations to do.

Our CAB has authority and, over time, knowledge but without responsibility it did not convince externally as a governance structure. It still fulfils a vital role in Slung Low’s activity: it provides the soul to all we do, but it cannot sit as the external guarantee that is an important part of governance.

So we continue to develop, grow, modify, test and adjust.

The solution to all of this may be found in the model of citizen assemblies. According to citizenassembly.co.uk these are ‘representative groups of people selected at random from the population to learn about, deliberate upon, and make recommendations in relation to a particular issue or set of issues. It is still up to elected politicians whether or not to follow the assembly’s recommendations.

The aim is to secure a group of people who are broadly representative of the electorate across characteristics such as their gender, ethnicity, social class and the area where they live. They could also match political divides like position on Brexit or Scottish independence’.

There are some important elements to this model that aren’t present in other forms of arts governance. Firstly, citizen assembly members are paid. This means that strategic oversight and planning of an organisation is removed from the realm of the evening meeting or the independently wealthy (or as is so often the case, the spouse of someone wealthy). Assuming there is cultural power in paying power is a double-edged sword. It’s a fool that thinks the employee is the most empowered role in society. However, it allows people to be full of care for the task because of the time the money allows.

The other element is the random nature of the process. People are drawn anonymously from a community in order to represent all the elements of the community involved. This puts diversity at the heart of the project. It also takes the emphasis off important individuals and puts it back on the process – this is also a useful strategy in our current political malaise. And because of that anonymous nature, the need for training and development becomes vital. It doesn’t assume (or ignore) the need for expertise. It secures it. It empowers its governance structure to know everything that you need from an oversight group by ensuring it.

Authority. With Knowledge. And as a result, you have a group capable of taking informed Responsibility. Responsibility that isn’t informed is just taking the blame.

If we’re going to have governance that isn’t held in the same minds and voices as those doing the work and making the connections, we need a governance structure that’s just as thoughtful and careful as the rest of our work.

The current ‘gold standard’ of governance is not fit for the sort of progressive, community-centred work we’re making; it isn’t right for the disruption to the status quo that we all know is needed.

The sector does not contain the good faith, the funders, the self-confidence, nor the clarity, for the Slung Low model of transparency and hope.

So the model of citizen assemblies, with its sophisticated understanding of authority, responsibility and knowledge may well point to a better future.

And if not that, then something else, because a change is needed.

Perhaps you know what it is. Let me know, yeah?